Watching a loved one face grief is one of the hardest things I’ve had to do. I find myself wanting to take the pain away, ultimately knowing,, that I can’t is SO hard and, let’s face it, pretty stressful. This week, it began with a phone call, the one that comes at a time of day when you immediately know something isn’t good before you even answer the phone. My body got tense, my shoulders raised, and my stomach in knots as I answered it. The call display made it clear that I would again need to give my husband awful news. This is the second time such a call has come; three years ago, his mom and now his dad.

I watched as the sad realization crossed his face; my heart broke for him. I could feel the responsibility of making something that wasn’t okay for him. To protect the person I love so much from pain and suffering. Which often comes with the memories of my own experience with loss and grief coming to the surface. Our stress usually begins in experiences we have no control over; they seem to take on their own lives. What I’ve learned through these experiences has helped me tremendously. And today, I want to release some of my emotions by sharing the strategies that have helped me with you.

What is grief?

Before I begin, let’s answer a question. What is grief? According to Wikipedia, “Grief is a multifaceted response to loss, particularly to the loss of someone or something that has died, to which a bond or affection was formed. Although conventionally focused on the emotional response to loss, it also has physical, cognitive, behavioral, social, cultural, spiritual and philosophical dimensions.”

Essentially it is our reaction to loss, any loss. The loss comes in many forms, the death of a loved one, the loss of a relationship, a friend, a job, or even a dream. Perhaps this is best described by the American Institute of Stress “Grief is intense and multifaceted, affecting our emotions, bodies, and lives.”

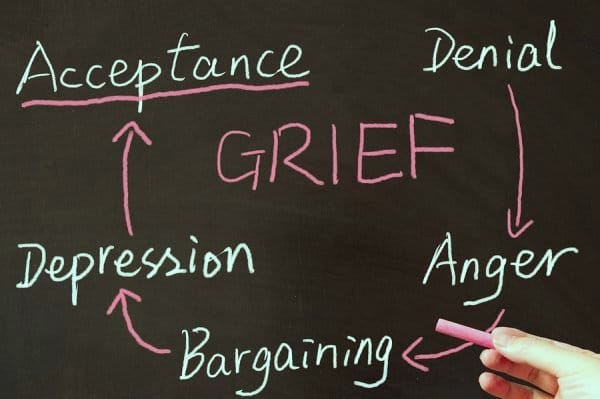

The five stages of grief

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross first proposed the five stages of grief in her 1969 book On Death and Dying. Interestingly, since writing the book, there have been significant changes in how she talked about her model. It is written like grief is a linear journey we experience, then we are done. But anyone who has experienced grief will tell you this isn’t true. We can learn from this model that there are five experiences with grief vs. stages like we are leveling up out of grief.

The truth is everyone grieves differently; we do not experience the stages of grief in the order listed below, which is perfectly okay and normal. The key to understanding the stages is not to feel like you must go through them in order. Instead, it’s helpful to look at them as guides in the grieving process — it helps you understand and put into context what we are experiencing.

My therapist described it this way. We will experience grief in our own way—some days, it will grip us tightly, making it hard to feel like we can function without the grip of grief, making it hard to breathe. On other days, it will feel like grief has less of a hold on us, and we are more able to live with the feeling of grief with us.

Denial & Isolation:

The first reaction is to deny the reality of the situation. “This isn’t happening, this can’t be happening,” people often think. It is a normal reaction to rationalize our overwhelming emotions. Denial is a common defense mechanism that buffers the immediate shock of the loss, numbing us to our emotions. We block out the words and hide from the facts. We start to believe that life is meaningless and that nothing is of any value anymore. For most people experiencing grief, this stage is a temporary response that carries us through the first wave of pain.

Anger:

As the masking effects of denial and isolation begin to wear, reality and its pain re-emerge. We are not ready. The intense emotion is deflected from our vulnerable core, redirected, and expressed instead as anger. The anger may be aimed at inanimate objects, strangers, friends, or family. Anger may be directed at our dying, or deceased loved one. Rationally, we know the person is not to be blamed. Emotionally, however, we may resent the person for causing us pain or leaving us. We feel guilty for being angry, and this makes us more furious. Remember, grieving is a personal process with no time limit or one “right” way to do it.

Bargaining:

The typical reaction to feelings of helplessness and vulnerability is often a need to regain control through a series of “If only” statements. This is an attempt to bargain. Secretly, we may make a deal with our higher power to postpone the inevitable and the accompanying pain. This weak line of defense protects us from the painful reality. Guilt often accompanies bargaining. We start to believe there was something we could have done differently to have helped save our loved ones.

Depression:

Two types of depression are associated with mourning. The first one is a reaction to practical implications relating to the loss. Sadness and regret predominate this type of depression. We worry about the costs and burial. We fear that, in our grief, we have spent less time with others that depend on us. This phase may be eased by simple clarification and reassurance. We may need a bit of practical cooperation and a few kind words. The second type of depression is more subtle and, in a sense, perhaps more private. It is our quiet preparation to separate and bid our loved ones farewell. Sometimes all we need is a hug.

Acceptance:

Reaching this stage of grieving is a gift not afforded to everyone. Death may be sudden and unexpected, or we may never see beyond our anger or denial. It is not necessarily a mark of bravery to resist the inevitable and deny ourselves the opportunity to make our peace.

Coping with a loss is ultimately a deeply personal and singular experience — nobody can help you go through it more easily or understand all the emotions that you’re going through. But others can be there for you and help comfort you through this process. The best thing you can do is to allow yourself to feel the grief as it comes over you. Resisting it only will prolong the natural process of healing.

Coping

Within the feeling of loss, you will likely feel a combination of emotions: depression, sadness, frustration, shock, fear, and even guilt. Your emotional stability will be affected, too; grief is often described as a roller coaster of emotions.

Your body reacts to grief, too; you’ll certainly feel tired. You can also feel physically weak as if all your strength has drained away and left you unable to do things you used to find easy. You could experience tightness in your chest, a change in your heartbeat, or difficulty breathing. You’ll either lose your appetite (or overeat to soothe anxiety). You can have insomnia or want to sleep away the days (and nights). You can find yourself crying at unexpected times, both publicly and privately. Mourners often retreat from their social lives, becoming increasingly isolated over time (complicating everything).

Moving through your grief can take weeks, months, or even years. Here’s the bad news: you’ll never completely get over losing your loved one. As Jandy Nelson wrote, “Grief is forever. It doesn’t go away; it becomes a part of you, step for step, breath for breath” (Source: Goodreads).

The strategies that have helped

Be gentle.

The first was recognizing that grief is full of experience and not a one-size-fits-all situation. This means that the approach can be day by day or even moment to moment and that how you process grief may not be the best fit for another. So for me, the most important part was being open to listening to your mind and body, allowing emotion to be felt. And for others to let their process take place, allowing your support to be guided by the curiosity of what they need now.

I am getting it all out.

I’m the type of person who needs to express my emotions verbally. But that doesn’t mean everyone needs the same kind of expression. Be creative in allowing yourself a way to tell how you feel. Maybe it is journaling, photography, painting, musical composition, or a more physical option like an intense bike ride or hike.

We are taking action to help others.

I’ve always found that volunteering or giving my time to others helps me relax and find perspective. Whether this means formal volunteering, dropping off a donation to the food bank, or spending time with the elderly, I have always found it helps connect me to my heart.

Enjoy some Movement.

We carry much of our emotions in our body, so when we feel stuck or caught up in emotion, or like it is too much to handle, I turn to movement. You don’t have to join a gym; it could be a walk or a yoga class. It could be some gentle stretching in your own home. Whatever you choose, be gentle with yourself and do something you enjoy.

Eating regularly.

Have you ever wondered why we offer to make food during a loss? Through experience, we know that the last thing we think about is taking care of eating. We may feel changes in our appetite or be so distracted by emotion that we miss the subtle signs our body gives us. Processing these emotions will require the energy we can only get from food, so eating small meals throughout the day are an important way to help us move through the process.

Ask for help and be gentle with yourself.

We are not our best selves when we are grieving. So I try to remember to be gentle with myself. It’s okay to cancel appointments, to take some time away from your responsibilities. Reach out to your support team and let them know how you feel.

Listen to and lean into your own needs.

It can be straightforward in these moments to overstretch ourselves caring for others. Take some time each day just for yourself. Listen to what you need, whether rest or just some time away. It’s okay to take this time to keep your cup full.

Disclaimer:

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinicians.